-

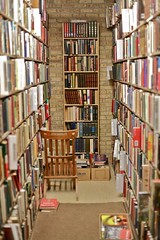

The Inmates Are Running the Asylum

Sometimes books sit on my shelf for a long time before I get around to reading them. This particular book sat mostly unread for about ten years. With a new software project starting up that desperately needs sensible design, I finally finished reading Alan Cooper’s The Inmates Are Running the Asylum.

Sometimes books sit on my shelf for a long time before I get around to reading them. This particular book sat mostly unread for about ten years. With a new software project starting up that desperately needs sensible design, I finally finished reading Alan Cooper’s The Inmates Are Running the Asylum.The book is more or less divided into two parts. The first part aims to persuade the reader that software products are severely lacking in good user interaction, and that much improved user interaction could theoretically exist; the second part aims to persuade the reader that something can in fact be done about this problem.

It’s like the fellow who leads a huge bear on a chain into the town square and, for a small donation, will make the bear dance. The townspeople gather to see the wondrous sight as the massive, lumbering beast shambles and shuffles from paw to paw. The bear is really a terrible dancer, and the wonder isn’t that the bear dances well but that the bear dances at all.

Cooper argues that software users have endured many technological dancing bears, and that these users end up as either “apologists” or “survivors”. The apologists are delighted that the software functions, and make excuses for its poor user interaction design, claiming that it’s not really all that bad, and you just need to be more computer literate in order to use it. The survivors are less persuaded about the goodness of the software, but they don’t want to appear stupid by complaining about it, so they just quietly put up with it.

The apologists say, “Look what the computer lets me do!” The survivors say, “I guess I’m just too stupid to understand these newfangled machines.” The apologists say, “Look at this! A dancing bear!” The survivors say, “I need something that dances, so I guess a bear is the best I’m gonna get.”

Unfortunately, most of the people involved with creating software lean more toward the apologist side, failing to understand how incomprehensible the software comes across to people who do not enjoy challenging themselves with computer interaction puzzles.

When left to their own devices, programmers build software the way that makes the most sense to them. They frequently do not “design” the user interaction aspect at all, but rather just start coding. That may work well enough for programming tools like compilers and debuggers and text editors, but software that is meant to be used by non-programmers should take into account how those users think, and what those users want to do with the software.

Confusing, poorly-designed software development can be especially problematic when building custom software used internally in a business, for it is being foisted upon employees who lack the option to avoid using it.

Badly designed business software makes people dislike their jobs. Their productivity suffers, errors creep into their work, they try to cheat the software, and they don’t stay in the job very long. Losing employees is very expensive, not just in money but in disruption to the business, and the time lost can never be made up. Most people who are paid to use a tool feel constrained not to complain about that tool, but it doesn’t stop them from feeling frustrated and unhappy about it.

Cooper recommends that deliberate design should be a major part of a software project, and that it should take place before any user-facing software is written. Further, the design would best be done not by programmers, who are expert in intricate, mentally-challenging details, but rather by dedicated designers, who are in position to better advocate for the users. (It is conceivable that programmers could also be good designers, but there is often too much conflict of interest.)

What to Do?

What would good design look like? The second half of the book is overflowing with helpful ideas. Hitting on a few topics:

-

Don’t design for specific literal users; instead, based on real users, invent personas — fictional characters that represent your users. These will help keep the design process grounded without trying to account for every possible detail of every possible actual user. Trying to build software that pleases all the people all the time is unwise, as there are so many different potential users. Instead, focus on as few users — or as few personas — as possible, and do everything you can to make sure your software is not only liked by them, but utterly and completely loved.

-

Not all tasks that a user needs to accomplish in the software are equal, and they should not be presented as equal. If a typical user spends 95% of their time accessing five features, and 5% of their time accessing twenty other features, then make those first five the most prominent. Also, since your time to design is not infinite, devote more time to designing those five features than to designing the twenty that aren’t used as much.

-

Software design should be documented clearly and completely. While programmers should be free to get creative with the software internals, anything that impacts how the user interacts with the software should be plainly spelled out. Which is not to say that the design is unchangeable, but rather, that it shouldn’t be ignored or taken as a mere suggestion.

-

Users do not necessarily know what they want, nor do they (any more than random programmers) necessarily have any clue about software design. Accordingly, software should not be developed just as a laundry list of features requested by users. Some requested features might be good to add to a software product, but some might not. If adding a feature would ruin an otherwise good design, then it should be rejected. Listen to users, and endeavor to meet their needs, but do not obey users. They aren’t in control of the software product development.

-

Some very large companies (such as Microsoft, especially Microsoft of the 1980s and 1990s) can afford to publish poorly-designed software, accept insults and ridicule from users, and iterate new, improved versions of their software until the users are reasonably happy with it. Most companies cannot afford to do this, but seeing Microsoft do it can suggest that it is the optimal way to develop new software. All companies, big and small, would be better off doing real design rather than just flinging software out the door to see what users think they like, but small companies especially can’t afford not to design. [This might not be as true as it once was, since starting a small software company is so much less expensive than it used to be. Nevertheless, if a good product can be made right away through design rather than iterating through several bad products, it stands to reason that the design phase is still valuable.]

Conclusion

Many ideas that Cooper recommends for better software design I see happening today. Progress is being made; software is better than it was ten years ago. But many of the problems of bad software design still linger on. Perhaps most disconcerting is that the very concepts of software design that Cooper outlines seem to be neither taught in computer science education, nor advocated for in common practice. Clearly some programmers, some companies, must be implementing ideas along these lines, but the status quo appears to still be apologist programmers skipping the design phase on the way to shipping dancing bearware, which may or may not get iterated into something good.

For software developers, I cannot recommend this book highly enough. I only wish that I had read it ten years ago, and maybe again every year since then. If you know a software developer, it’s not too late to get free Amazon shipping before Christmas.

Bonus: Song Lyric Meanings

I think it is now clear that, written in 1960s, Randy Newman’s song Simon Smith and the Amazing Dancing Bear is in fact about a programmer who skipped the design phase, dumping ill-conceived computer software on unsuspecting users:

-

-

The Chosen Few

Ever on the lookout for sound reasoning to support my book-buying habit, I just finished reading The Chosen Few: How Education Shaped Jewish History. If you’re expecting a casual read, this book gets a bit academically verbose at times, but stays sufficiently action-packed so as not to get boring.

Ever on the lookout for sound reasoning to support my book-buying habit, I just finished reading The Chosen Few: How Education Shaped Jewish History. If you’re expecting a casual read, this book gets a bit academically verbose at times, but stays sufficiently action-packed so as not to get boring.The central theme of the book revolves around the Jewish religious mandate that children be educated in reading and study of the Torah (i.e., the Jewish Bible), and how that this education, which was not required in other religious or cultural societies, led the Jewish people toward high literacy in general. This, in turn, made them fit for the most profitable occupations wherever they lived.

Running parallel with that main theme, the authors make the case that, while high literacy may be of spiritual value anywhere, it is only of financial value in developed, urban areas. Highly literate people may be well suited to work as bankers, physicians, and engineers, but if the only industry available as far as the eye can see is farming, then there’s not a lot of opportunity to engage in such high-paying work.

So Jewish people have, historically, sought to live in highly populated areas where they could make the most use of their literate professions. But not only have they sought out highly populated areas, they have sought out highly populated areas that were not already saturated with other (typically Jewish) people doing the same work. A city might have need for ten bankers, say, but perhaps not a hundred. This, the authors contend, played a significant role in Jewish people migrating to numerous disparate areas, rather than all sticking together in the same place.

But while they may not have all lived in the same cities, they remained connected. This, the authors explain, has been another factor in Jewish financial success over the years: they frequently networked with each other, meeting in person from time to time, but mainly through writing letters. They shared details about what goods were in most demand in a region, so that traveling Jewish merchants could be equipped to sell what people were most likely to buy.

They also maintained close connections with their spiritual leaders, those responsible for interpreting the Torah and Jewish traditions and offering guidance on how to conduct one’s life and business.

Finally, Jewish religious structures provided a framework for forming and enforcing contracts, which proved helpful as literate Jewish businessmen moved into perhaps their most profitable enterprise of lending money, to be repaid with interest. Of this occupation, Rabbi Joseph b. Samuel Tov Elem Bonfils wrote circa 1040:

Money lent on interest is profitable, because the pledge remains in the hand of the creditor, and the principal increases without effort or expense.

The work of being a merchant, or a craftsman, or a physician, or an engineer, required regular time and effort put into the job. The work of lending money involved filling out paperwork and keeping good records, but mostly doing nothing at all while payments came in.

In the time period that the book covers, there was a fairly sharp contrast between people who were “literate” and people who were “illiterate”, with the illiterate people being literally illiterate. In the final chapter, the authors hint at what will come in a future volume covering the years from 1492 through today, suggesting that while society as a whole has become more literate, Jewish people have persisted in seeking to be maximally literate; i.e., pursuing higher education and the most lucrative occupations intentionally.

What can we learn from this book to apply in our own lives? I think the most obvious takeaway is that it is good to cultivate a practice of learning, and especially learning things that would be the most beneficial, the most useful, the most profitable. Is the company that you work for opening a branch office in Brazil? Perhaps it would be worthwhile to study some Portuguese. Are you looking for employment in web development? While there’s plenty of PHP code still out there, the future looks brighter for JavaScript and Ruby.

But there are also some open problems for how we might apply the principles described in the book today. Some professions, such as physicians, will always be local to specific physical communities, but the world is increasingly flat. Local merchants are up against online retailers. Much professional work can be done entirely on computers, opening the door for the work to be done not by merely the best professionals in the city, but by the best professionals on the planet. (Or, alternately, the least expensive professionals on the planet…) The notion of being the best, most literate professional in a city, catering specifically to the people of that city, might not carry as much weight when candidates to do the job can be selected from any city at all.

On the other hand, the advantage of lending money as a business, namely that “the principal increases without effort or expense,” can be applied to many more fields today, by way of creating and selling digital products. Literate experts in any field can make books and software applications and multimedia products, which can be sold many times over without incurring any significant effort or expense beyond the initial production.

Other random tidbits from the book that I found interesting:

-

Over some of the time span covered, the cost of buying a book was routinely 2-4 times that of a typical monthly salary. This made education an especially costly activity!

-

Even around the first century, the Hebrew language was not heavily used by the Jewish people. As is common (at least in the United States) today, it was mainly used for reading and studying the Torah, and not so much for everyday writing and talking.

-

Jews were explicitly welcomed by many eleventh-century rulers in Germany. Bishop Rudiger of Speyer wrote a charter in favor of the Jewish people, which concluded with, “Lest any of my successors diminish this gift and concession … I have left this charter as a suitable testimony of the said grant. And that this may never be forgotten, I have signed it, and confirmed it with my seal as may be seen below. Given on September 15th, 1084.”

I found this book enjoyable and thought-provoking, and am looking forward to the sequel. I read a paperback edition, but the book is mostly plain text, with a few charts and maps, and would probably render well in Kindle format also.

-

-

Old Avid Software on Mac OS X El Capitan

Little strikes fear in the hearts and minds of music production engineers like upgrading to a new version of Mac OS X. Will their precious (and often expensive) music software applications continue to work as expected, or will they fail in some unforeseen catastrophic way?

Little strikes fear in the hearts and minds of music production engineers like upgrading to a new version of Mac OS X. Will their precious (and often expensive) music software applications continue to work as expected, or will they fail in some unforeseen catastrophic way?I usually wait months — if not years — before upgrading to a new OS X release, but since I do work not only with music but also with software development, I wanted a newer version of Apple Xcode, which I had been delaying installing for the past year, concerned about upgrading my operating system to OS X Yosemite. When Apple released OS X El Capitan earlier this week, I figured I might as well jump all the way to El Capitan, and fight whatever software update battles may lie ahead.

So how did things turn out?

-

Avid Sibelius First 6: The “lite” version of Avid Sibelius, I have been running this for several years. I was pleasantly surprised to find no problems running this under El Capitan.

-

Avid Pro Tools 10: With Avid up to Pro Tools 12 now, I strongly suspected that Pro Tools 10 might explode in some horrific way, and, with credit card in hand, was prepared to upgrade if necessary. Again though, I was pleasantly surprised at the outcome. As was reported under OS X Yosemite, there are some minor graphical glitches when browsing menus, but that problem is reasonably surmounted. Otherwise the software seems to work as expected. I recorded a quick demonstration piece in Pro Tools, which also exercised Native Instruments Kontakt 5, Addictive Drums, and Valhalla Room reverb.

-

Adobe Lightroom 5: Not an audio application, but another major piece of software that I use frequently. No issues under El Capitan that I can see.

[In every case, the software had already been installed as of my previous Mac OS X Mavericks setup, which I upgraded to El Capitan. I have heard that at least some older Avid software won’t install from scratch on El Capitan.]

The biggest surprise was when I turned on my Focusrite Saffire PRO 40 audio interface, and the Saffire mix control software on the computer failed to see the hardware unit. Focusrite’s website claims that the Saffire PRO 40 works under OS X El Capitan with the latest Saffire MixControl 3.6 software, which I installed, so what was wrong?

I eventually found a helpful tidbit elsewhere on Focusrite’s website that explains, when upgrading MixControl software, there is an old library file that you need to manually delete before the hardware connection works properly. I followed the instructions, and all was well.

The bottom line: I could easily continue using all of the old software applications that I have tried so far under OS X El Capitan without significant issue. I will probably upgrade to Pro Tools 12 (or possibly move to another DAW package) soon, but Pro Tools 10 is still quite functional, so no hurry.

-

-

The Dog Wars

After thoroughly enjoying Donald McCaig’s book Eminent Dogs, Dangerous Men, I just finished reading a sort of sequel, The Dog Wars: How the Border Collie Battled the American Kennel Club.

After thoroughly enjoying Donald McCaig’s book Eminent Dogs, Dangerous Men, I just finished reading a sort of sequel, The Dog Wars: How the Border Collie Battled the American Kennel Club.Never having come across reason to believe otherwise, I had thought of the AKC as a respectable organization that advances knowledge of dogs and promotes their well-being. I cheerfully accepted AKC STAR Puppy status on behalf of my own border collie after she completed a puppy training class. So I started reading this book under the assumption that border collie owners “battled” the AKC in an effort to make the AKC recognize and accept their dog breed. In fact, most United States border collie owners — at least those who gave the matter any thought at all — were adamantly against border collies being officially recognized by the AKC.

Border collies have traditionally been working dogs, bred especially with sheep herding in mind. For most of their history, little if any regard was given to what they color they were, how big they were, what manners they had, or any attributes at all except how well they did at herding sheep. Could your dog excel at this task? Then that dog might as well be a border collie. [I personally imagine that, at an old-school sheepdog trial, even a pig might have been more welcomed than some might have us believe…]

The main official function of the AKC has long been to maintain registrations of dogs, for the purpose of demonstrating that a dog was “pure” in breed, and of some particular lineage. In practice, McCaig describes, many activities of the AKC revolve around hosting show events that are driven by exhibiting dogs for their appearance and physical attributes as opposed to for what they can do. At best, breeding dogs for appearance can hinder their specialized behaviors (like herding sheep), as such traits do not necessarily go hand-in-hand, genetically speaking. But worse, breeding dogs for appearance can introduce physical malaties, resulting in dogs with sundry genetic diseases.

As in his previous book, author McCaig himself played a role in the story, as he was significantly involved in spearheading an effort to prevent the AKC from accepting dog registrations of border collies, lest the working utility of the breed be diminished and the risk of poor genetic health be increased. The Dog Wars paints a picture of an utterly idiotic American Kennel Club, which seems to not be able to care any less about the long-term well-being of border collies, and which seems to, for reasons not made clear (either to us the readers or, apparently, to McCaig) stubbornly insist upon incorporating border collies into its ranks.

Over several years in the early 1990s, McCaig sought legal counsel and assistance, and help from existing border collie registration associations which concurred that little or no good was likely to come from the AKC accepting their dogs. Unfortunately, the story comes to a somewhat anti-climactic ending when one of the three major border collie registrars seems, while agreeable to the cause, insufficiently interested in providing their support until after the AKC had already started registering border collies. The legal plan fizzled out with nothing further to be done.

But while the border collie proponents may have lost the war with the AKC, they won plenty of smaller battles, and still did much good. Through publishing articles about their cause in newspapers nationwide, and eventually gathering attention from national television news programs, their concerns about breeding dogs purely for appearance became more widespread. Public interest in “pure-bred” dogs decreased, and acceptance of dogs of “lesser” pedigree rose. In the end, while the American Kennel Club began registering border collies, most border collie owners ignored the AKC, and continued using the long-established border collie registrars, and attending their own self-governed sheep herding events rather than joining the AKC shows. So much of the risk that McCaig and company were concerned about was mitigated not by winning their plea against the AKC, but by better educating the people whose dogs might have otherwise been negatively impacted.

The book is also peppered with side-stories about dogs (mostly border collies, of course) that don’t have anything in particular to do with the main theme of going up against the American Kennel Club. In a poignant style typical of his previous book, McCaig shares about his border collie Silk whose life was drawing to a close. She was not particularly discerning about food, and had little interest for toys. What could he possibly do to make her feel more appreciated, more loved?

Silk liked it when [my wife] took her on solo walks because, in a four dog pack, it was a privilege to be walked alone. I took her out for training. I’d stand in the middle of our flock and signal her: go left, go right. I’d show her the bottom of my palms: lie down. I’d signal her to walk up on her sheep; when they broke, she’d cover them. The old, deaf, dying dog ran around the sheep until her tongue hung out.

Afterwards, she’d come up to me for a pat and she was quite pleased with herself: “Aren’t I such a good sheepdog?” …

All that we can give a dog that the dog will value is our time.

Is the AKC of today the same misguided organization that McCaig tells us about? My limited experience with them as been positive, and this book describes events that took place twenty-some years ago. Judge for yourself, but beware judges — AKC or otherwise — who value your dog’s appearance over your dog’s health, or the health of the entire breed.

-

Josh Renaud on Electric Dreams

Friend and former classmate Josh Renaud was recently interviewed on sundry topics related to Atari computers and electronic bulletin board systems. I never got into the BBS scene much myself, but Josh’s enthusiasm nevertheless conjures up feelings of nostalgia for the exciting early days of personal computing.

A much enjoyable and educational interview, well worth a listen!